Are you the person wearing a jacket in the summertime and fighting with co-workers to turn the air conditioner off? It’s possible your thyroid is the culprit behind your cold and heat intolerance.

As the master regulator of your metabolic health, your thyroid plays a direct role in thermal regulation. Thermogenesis, or the creation of heat, is a byproduct of metabolism. As the body metabolizes to produce energy from the energy you consume from food, heat is emitted. Metabolism is complicated, but put simply, when you eat, you’re consuming calories. Calories are a measurement of energy that a specific food provides. Calories (actually formally known as kilocalories which = 1000 calories or 1 Calorie) is the amount of energy needed to raise 1 gram of water 1 degree Celsius. Quite literally, calories are a measure of heat potential a certain food creates.

When thyroid levels are low, the metabolism slows down, resulting in lowered body temperatures. As thyroid hormone levels come within the normal range, body temperature follows suit. Low thyroid levels are caused by multiple factors including nutritional deficiencies, stress, and autoimmune disease that leads to thyroid destruction and impaired hormone output.

Remember, your body is designed for survival and adaptation, so when stress is high and/or nutritional intake inadequate to match demand and/or food intake is inconsistent (for example, yo-yo dieting) and/or there are key nutrient deficiencies that impair hormone creation, the body compensates by slowing down metabolism via a decrease in circulating thyroid hormone levels. So, while you may intentionally be exercising like crazy and cutting calories to lose weight, the memo your body receives is, “We are running away from a threat and there is not enough food”. Enter: preservation mode. Being in “preservation mode” means that functions slow down to conserve energy. This includes, but is not limited to, energy production, digestion, muscle building, and hormone production— just to name a few.

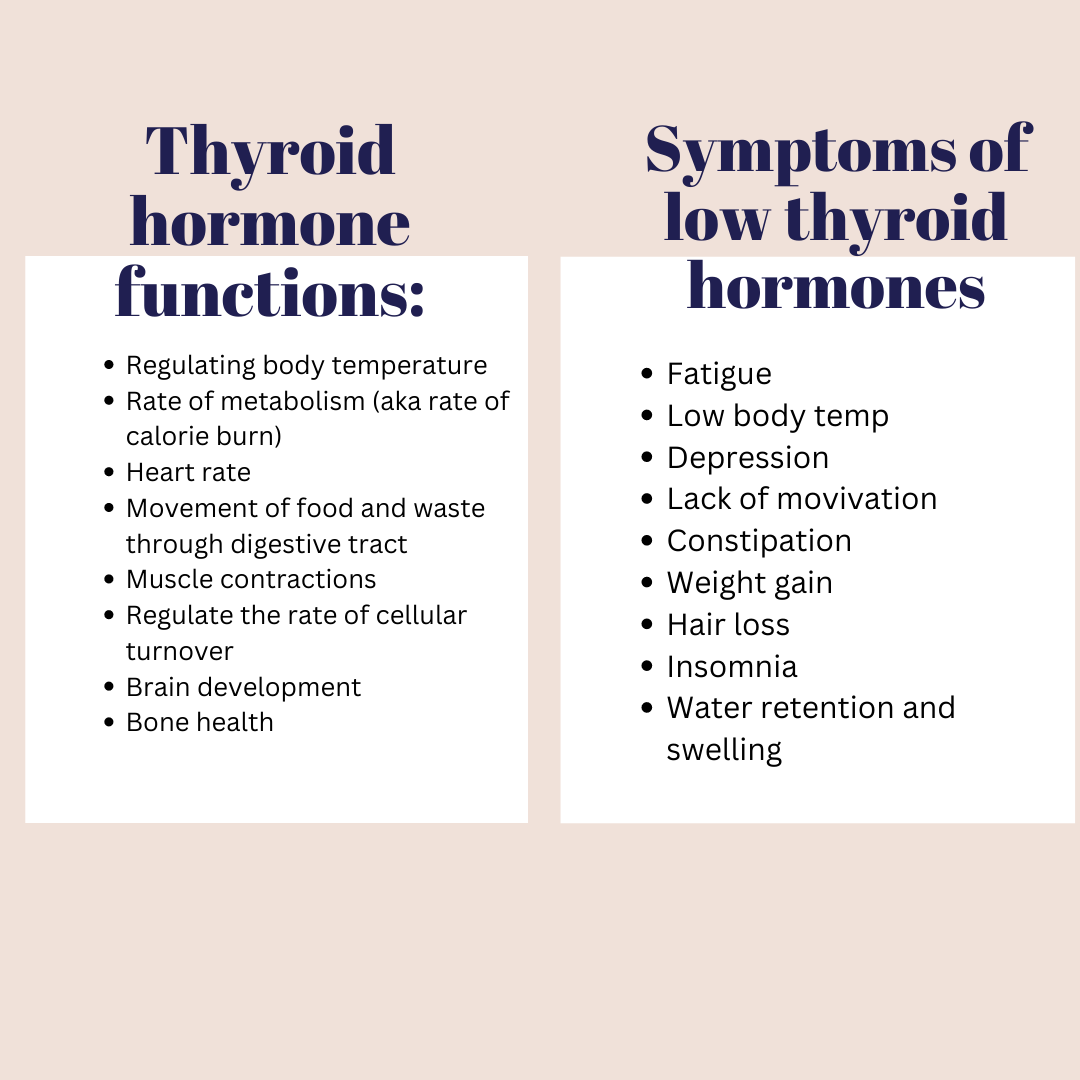

Thyroid hormone functions in the body:

Symptoms of hypothyroidism:

Assessing a full thyroid panel is an incredibly helpful way to determine thyroid status, but there are a few drawbacks to relying on those numbers alone. First, is the difficulty of getting labs done due to financial constraints, getting a proper order, and the fact that it’s unrealistic to get labs drawn on a frequent basis. Second, is that various factors affect values. For example, TSH is more a marker of pituitary (brain) function as opposed to true thyroid hormone status. Many factors, including stress and under-eating, can suppress TSH secretion from the pituitary gland. This is a survival adaptation. After all, the last thing your body wants to do when stress is high is to sacrifice energy stores if there is a possibility of low food supply. When stress is high and food is scarce, the body protects itself by slowing metabolism to conserve energy. The transport of thyroid hormone across brain cells uses passive diffusion (no energy required) while cells require active transport (needs energy/calories). Therefore, the TSH value can appear normal because the brain is getting what it needs while the cells in the periphery (muscles, organs, etc.) are hypothyroid. Lastly, even assessing T4 and T3 on lab testing has drawbacks because the lab is looking at serum (outside the cell) versus intra-cellular values. The transport of thyroid hormone into the cells requires energy (calories), electrolytes (sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium), and can be blocked by inflammation, stress hormones, and even from receptors being saturated with too much hormone (often the case if medication dosing is too high).

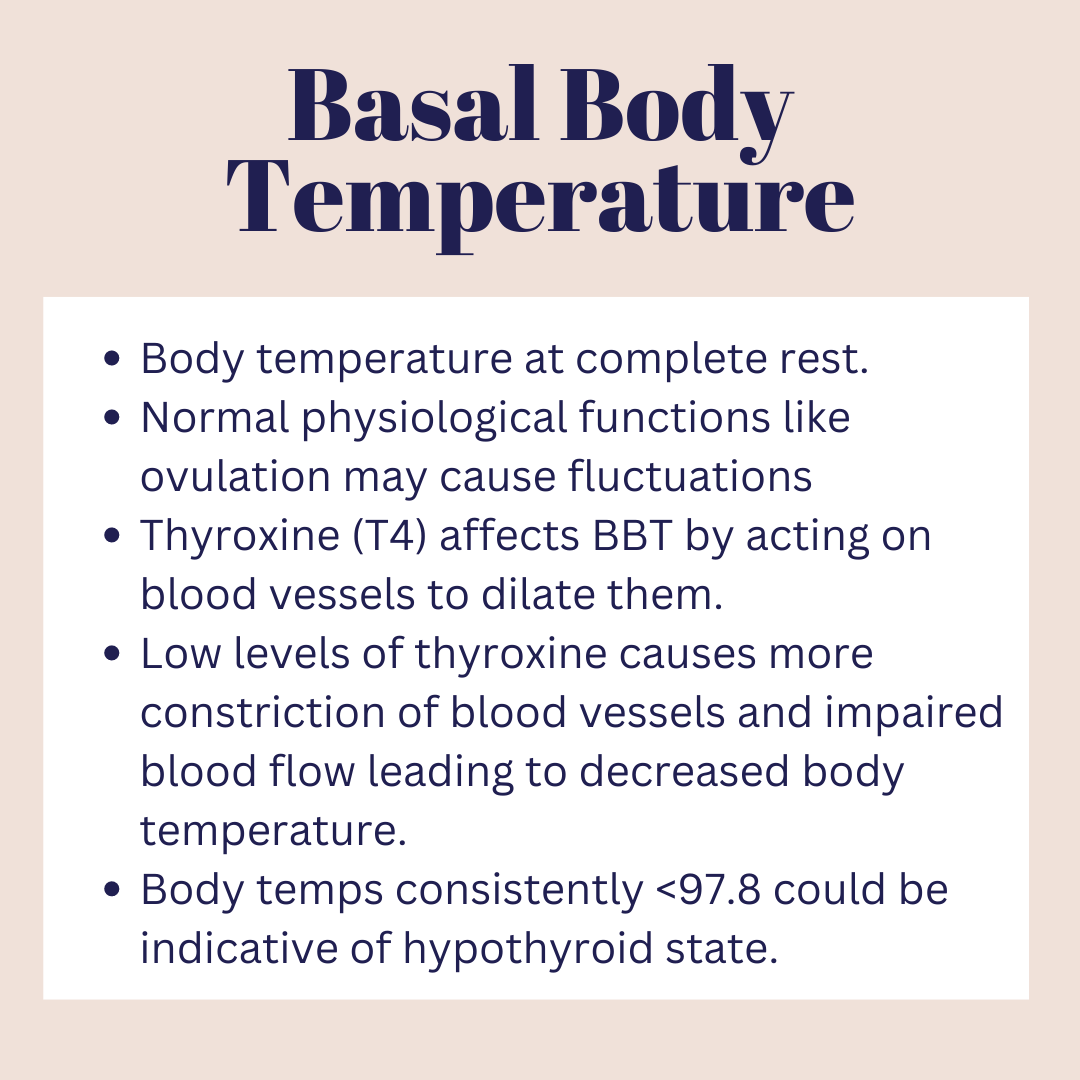

The moral of the story: labs are immensely helpful, but your experience (symptoms) and non-lab cues from your body (like basal body temperature) are a valuable piece of the puzzle to gauging your metabolic health on a more consistent basis. Together, all of these provide a clearer picture. Body temperatures and assessing symptoms are a non-invasive and inexpensive way to frequently check in with yourself.

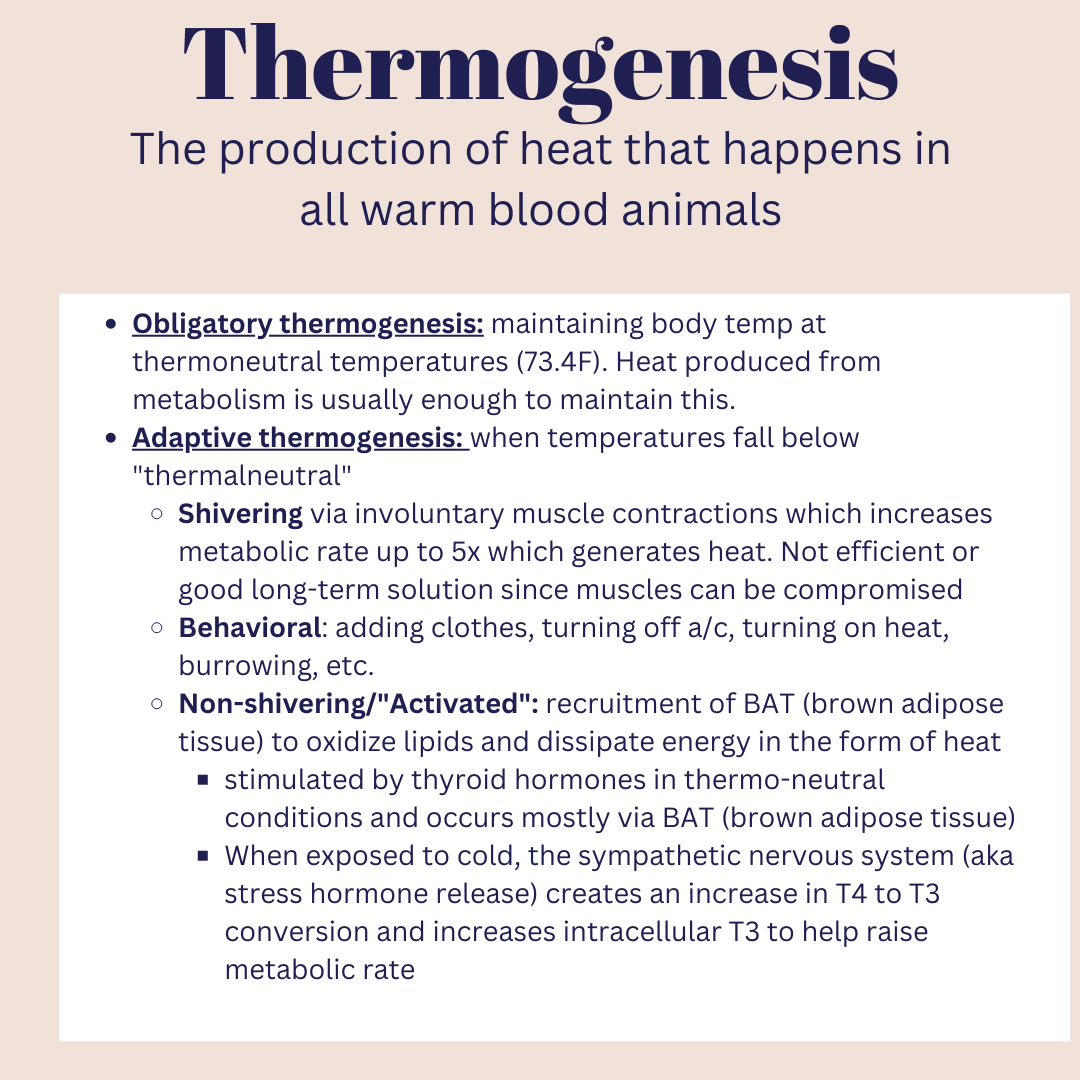

As a recap, thermogenesis is the production of heat that occurs in all warm-blooded animals. As warm-blooded beings, we are capable of maintaining euthermia (normal body temperature) from heat produced via metabolism called “obligatory thermogenesis”. When exposed to temperatures below ambient temperatures (73.4F, on average), obligatory thermogenesis may not be enough to maintain internal temperatures, so behavioral changes (including adding more clothes, applying heaters, turning off air conditioners) are usually triggered. Beyond that, metabolic adaptations include “adaptive thermogenesis” and “activated thermogenesis”.

Adaptive thermogenesis includes shivering and non-shivering reactions. Shivering is involuntary muscle contractions that generate heat and increase metabolic rate up to 5x. The downside of shivering is that it is finite due to muscle integrity being compromised over a long period of time. Additionally, because of the increase in metabolic rate, if there was food scarcity as well, it would be an inefficient way to produce heat because it would require high amounts of calories to support the continued action.

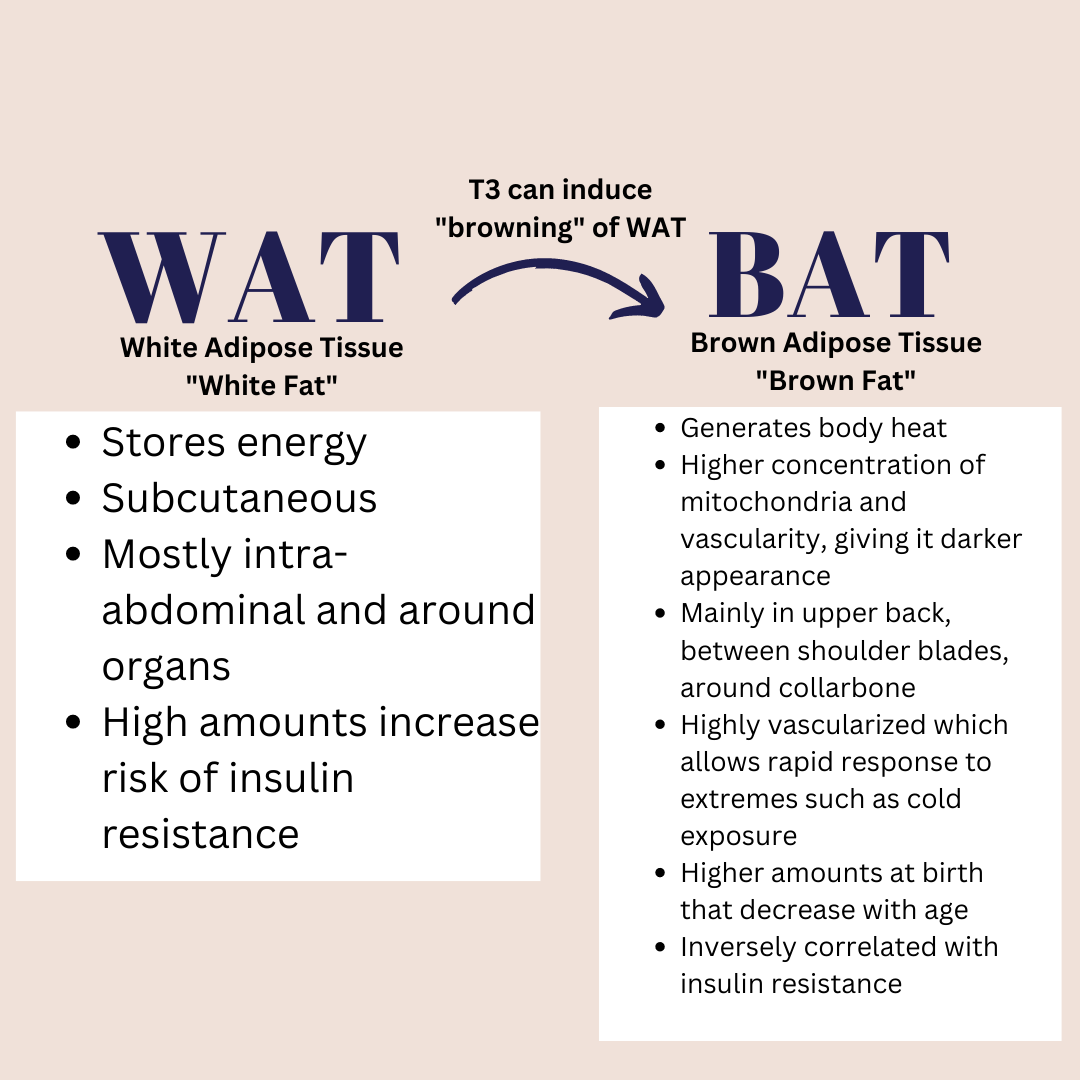

Non-shivering adaptive thermogenesis occurs in brown adipose tissue (BAT). The BAT is able to oxidize lipids (AKA use fat) as a source of energy and heat. BAT (brown adipose tissue) and WAT (white adipose tissue) vary in function, appearance, and metabolic activity. BAT generates body heat and is negatively associated with adiposity. It is found mostly in the upper back, around the neck, ribs, and heart area. It contains a high concentration of mitochronria and vascularity, which gives it a darker appearance and where the term “brown adipose tissue” comes. Humans have a higher amount of BAT at birth and it decreases over time, but certain practices can help to maintain and even increase BAT. In contrast, WAT (white adipose tissue) is a storage of energy. It’s stored mostly subcutaneously and around organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines. Higher amounts of WAT are associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Under certain conditions, WAT can undergo “browning” and turn into BAT or be a combination of WAT and BAT (called “beige fat”).

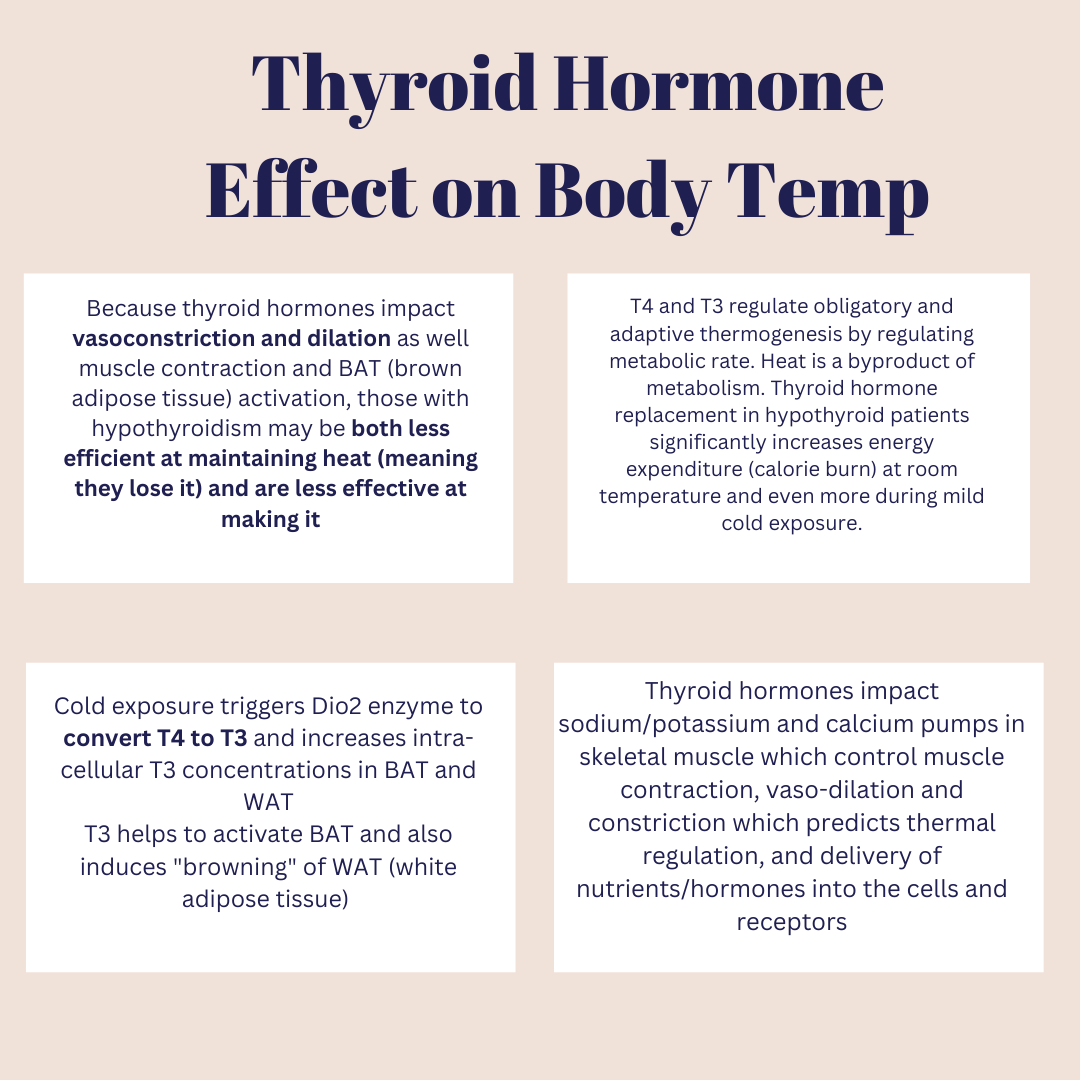

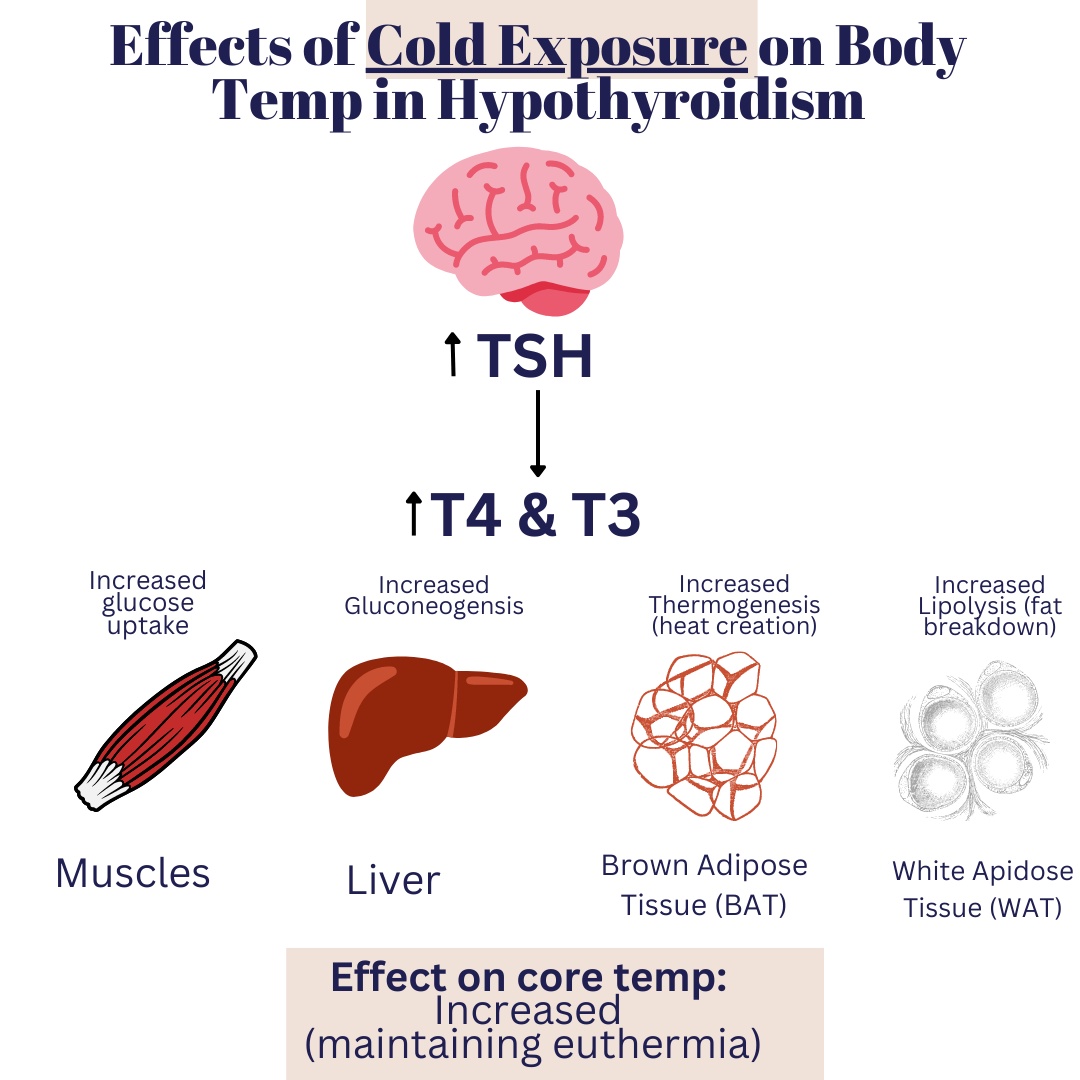

Thyroid hormones act on BAT and WAT to trigger the process in which heat is produced. Cold exposure stimulates an increase in DiO2 enzyme that converts T4 hormone into T3 and increases intracellular T3 levels. T3 acts to regulate BAT activity, so higher levels increase BAT heat production.

Thyroid hormones regulate vasodilation (widening) and vasoconstriction (constriction) of blood vessels. This blood flow largely regulates body temperature, so those with hypothyroidism are both less efficient at maintaining body heat (meaning they lose it easily) and are less effective at creating it.

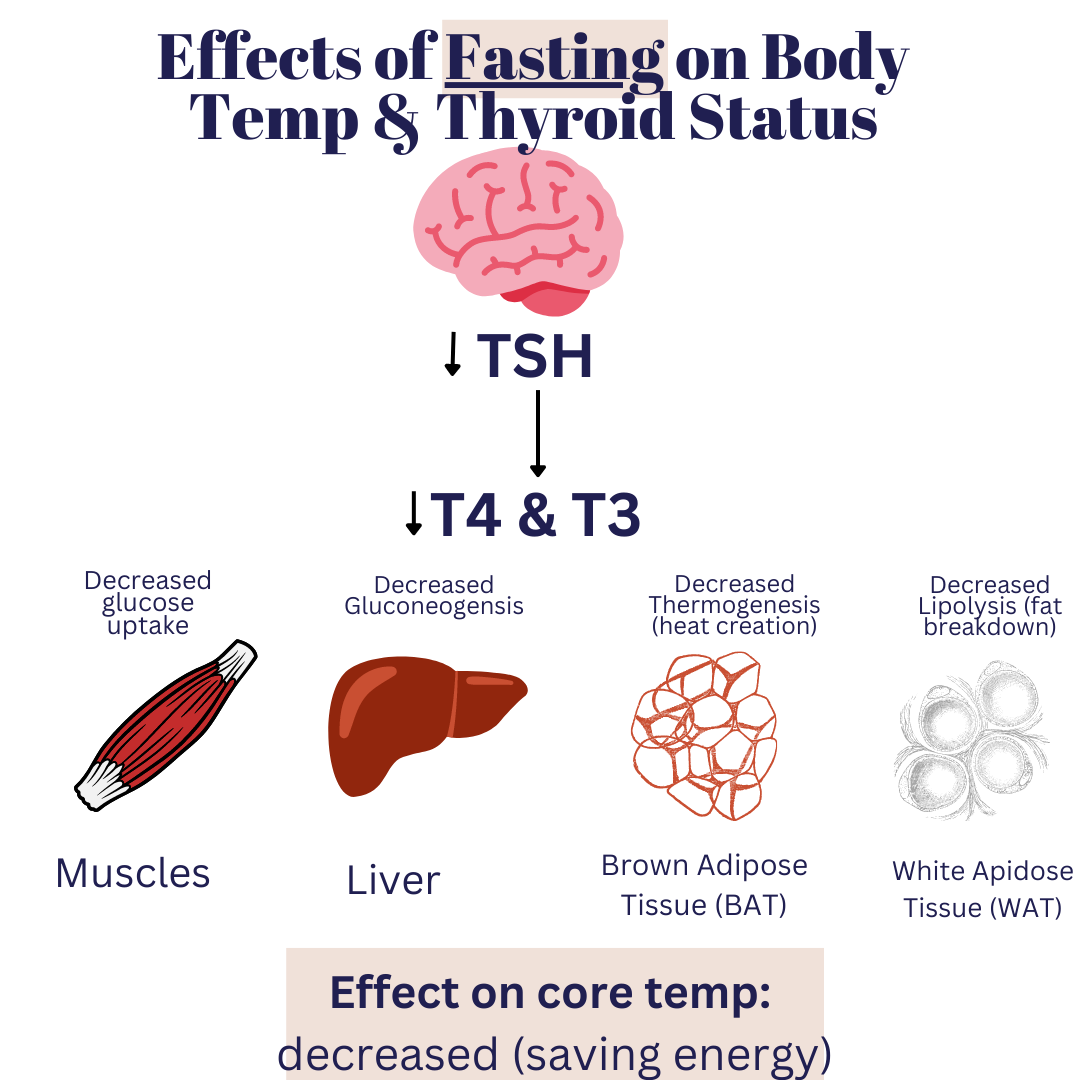

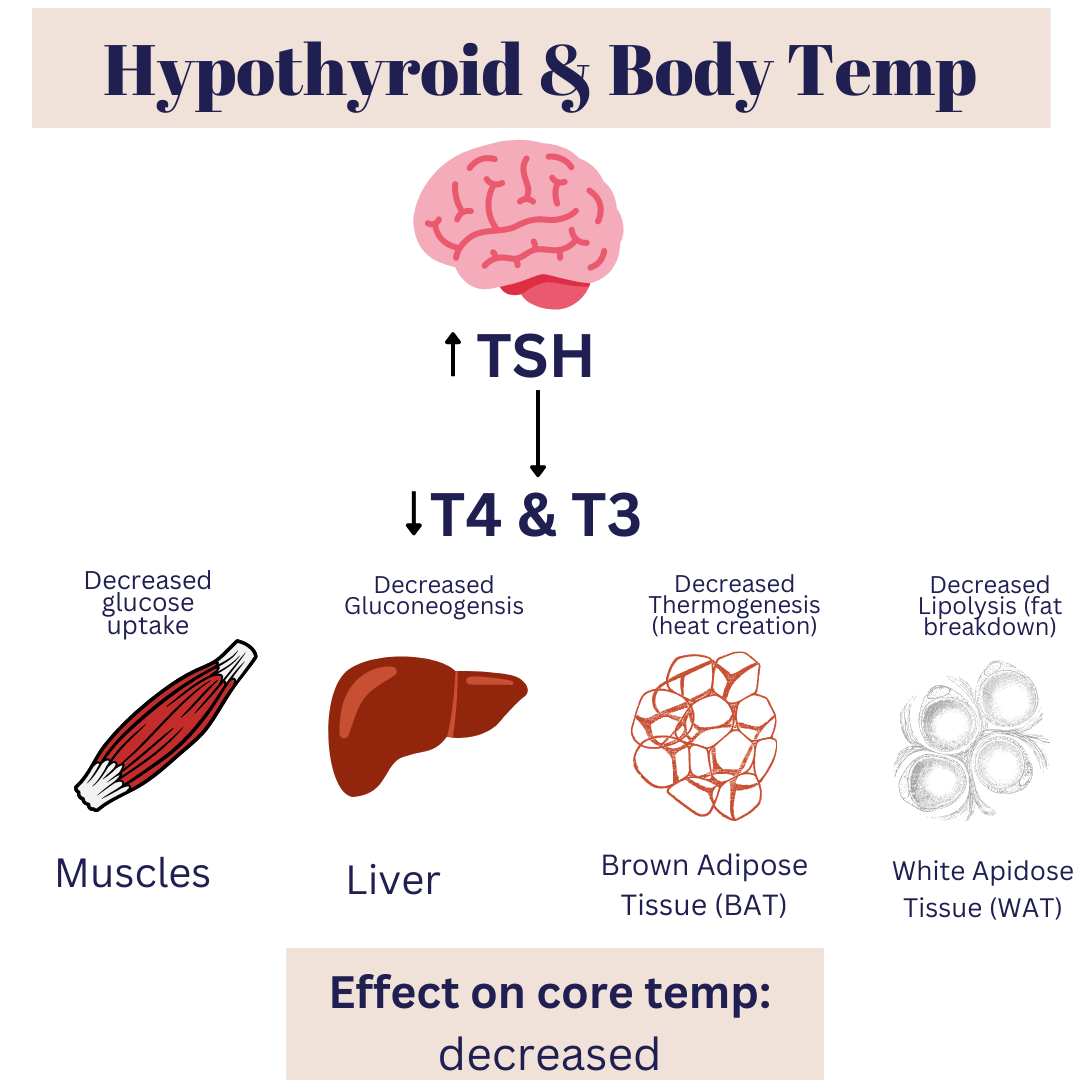

In true hypothyroidism (when there are low thyroid hormones and high TSH) there is a decrease in glucose uptake, gluconeogensis (creation of glucose), lipolysis (fat breakdown), and less heat creation. Theoretically, replacement of and/or optimization of endogenous thyroid hormone levels should normalize body temperature. This may be easier said than done since so many factors go into production, conversion, absorption, and utilization of thyroid hormones. A lot of times, this requires the help of a professional to identify your root causes, assess labs, listen to symptoms, and provide personalized recommendations.

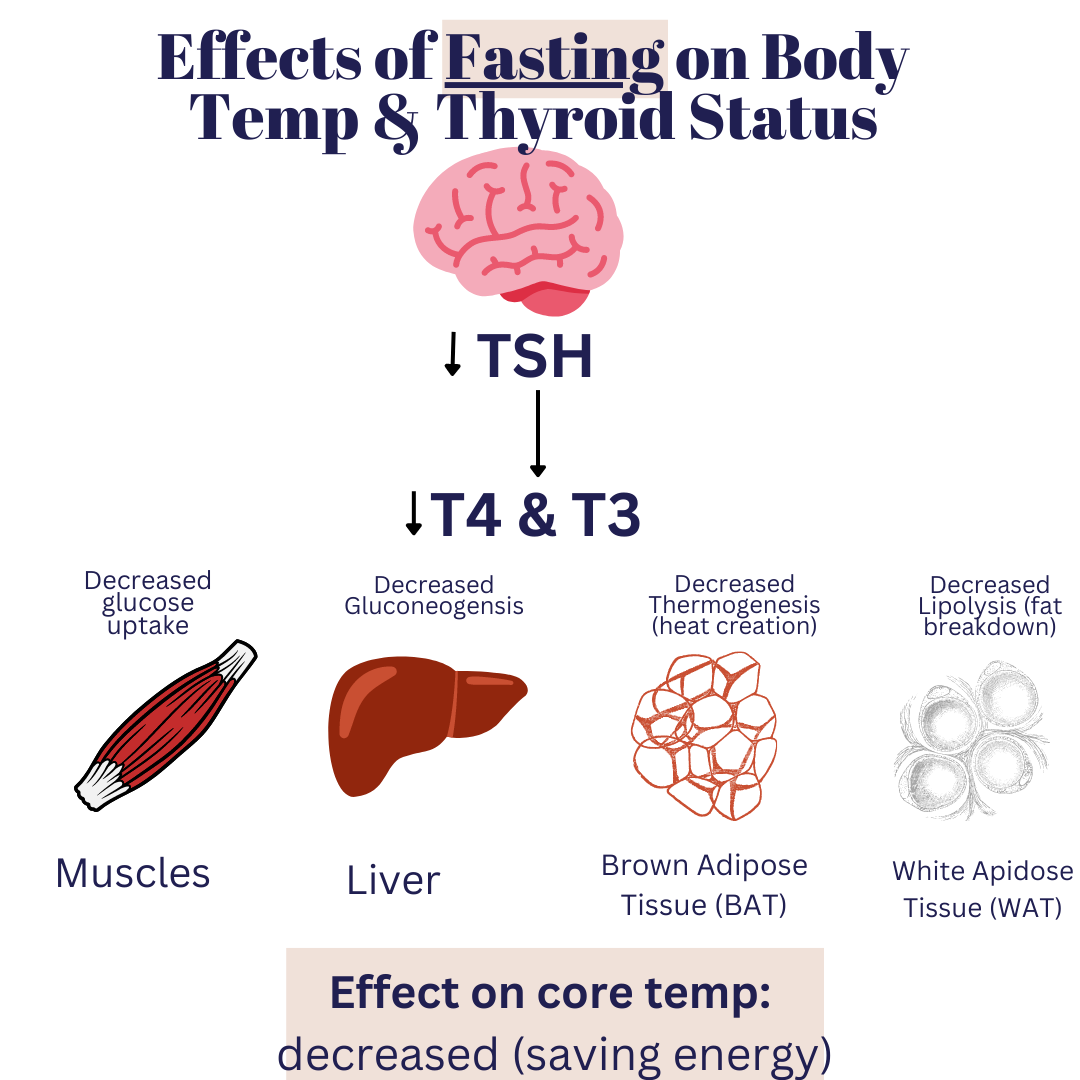

Another situation is in an initially euthyroid situation (normal thyroid status) and the effect on thyroid hormone status from fasting. Fasting leads to a decrease in TSH, a decrease in T4 and T3, as well as similar effects on glucose production, fat breakdown, and body temperature. Therefore, chronic under-eating can create a hypothyroid situation from an adaptive body response. Chronic low body temperatures can be a sign of low thyroid status, and can also be a sign of chronic under-eating. Beyond that, there can be nutritional deficiencies at the cellular level that give the impression of under-eating, despite adequate calories coming in!

Lastly, the impact of cold exposures on thyroid hormones shows that cold exposure increases the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to up regulate production of TSH which triggers more T4 and T3 to induce thermogenesis from that BAT. In fact, studies show that there may be a bi-directional relationship between BAT and thyroid hormones— that thyroid hormones don’t just affect BAT levels, but that BAT can actually increase TSH and thyroid hormones! That in mind, everything in moderation! Too much of a “good” thing isn’t good. Long-term, chronic cold exposures can stimulate increases in subcutaneous fat as an insulator to vital organs, so moving to Antarctica won’t heal your thyroid and solve any weight management problems 😉

1. Your body is designed for adaptation. Maybe your symptoms are your body’s way of doing what it’s designed to do… adapt! Eating enough food consistently is a foundational step to improving body temperature. Calories we get from food influence the calories (and heat) we burn and produce. Therefore, intentional under-eating, chronic skipping of meals, or being in an accidental calorie deficit (not eating enough to match the energy demands of exercise, for example) can result in the body becoming more energy efficient (AKA burning less fuel and creating less heat).

3. Short, intentional cold therapy can help to stimulate BAT (brown adipose tissue), which helps with thyroid hormone levels. This is best done in a well-fed, low stress state. If you’re skipping meals, not sleeping, and really stressed, this may not be the best option for you. Keep in mind— those with hypothyroidism are more susceptible to hypothermia, so be sure to do this safely! One of my favorite ways is to alternate hot and cold in the shower. Nothing crazy— just turn the water cold for 15-30 seconds.

4. Optimize your thyroid hormones to help with your body temperature. This may involve getting to a “sweet spot” with your medication. Chat with your doc about this! Also, figure out the root causes of your hypothyroidism to figure out the best approach for you!

5. Factors that you can control nutritionally include: balancing blood sugars, regulating inflammation, adrenal resiliency, intestinal support, and nutrient repletion. All of these I cover extensively in my 1:1 and virtual course using my “The BRAIN Method” approach. Everyone’s root causes of hypothyroidism are different, so management approaches are different.

6. Get some cold hard data (no pun intended) on your body temperatures to help fine tune your body literacy. You can either use an oral basal body thermometer and take your temps first thing in the AM before you’re out of bed. Another really nifty option is the Temp Drop. It tracks your temperature and symptoms along with your cycle to help you understand how different points in your menstrual cycle affect how you feel and function.

Disclaimer: Please note that “Thyroid School” emails & blogs from Chews Food Wisely, LLC (and Nicole Fennell, RD) are not intended to create any physician-patient relationship or supplant any in-person medical consultation or examination. Always seek the advice of a trained health professional with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition and before seeking any treatment. Proper medical attention should always be sought for specific ailments. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking medical treatment due to information obtained in “Thyroid School” emails. Any information received from these emails is not intended to diagnose, treat, or cure. These emails, websites, and social media accounts are for information purposes only. The information in these emails, websites, and social media accounts is not intended to replace proper medical care.

References:

EMAIL:

hello@chewsfoodwisely.com

VIRTUAL APPOINTMENTS ONLY

Business Mailing Address:

2525 Robinhood Street

Houston, Texas 77005

© 2025 Chews Food Wisely. All Rights Reserved. Website Designed by Brandify Collective

Disclaimers | Privacy Policy | Terms of Purchase | Terms and Conditions